Trade, Trump, and Soy

Trade was one of the hottest topics in the 2016 campaigns, both primaries and in the general election. Unlike nearly every previous post-war president, President-Elect Trump appears poised to continue his campaign rhetoric on trade once in office. Row-crop agriculture is unusual in that it is both typically a small family business and is highly export dependent. Were a trade war to break out between the US and China, recent experience indicates that agriculture, and particularly soybeans, would be an early casualty. This article explores the international soybean trade to try to understand how a tariff or embargo might affect US soybean producers.

In 2002, President Bush placed an import tariff on steel coming in to the US to protect US producers under section 201 of the 1974 Trade Act. Section 201 was created so that the US government could grant temporary protection to industries who were being gravely harmed by trade, in order for them to adjust and adapt. The EU was the first to file a suit at the WTO against the US tariffs. In November of 2003, the WTO ruled for the EU, and allowed the EU to impose tariffs up to a total of $2 billion. The EU published a list of targeted products, and they were very specific, meant to harm Bush in swing states in the 2004 elections.

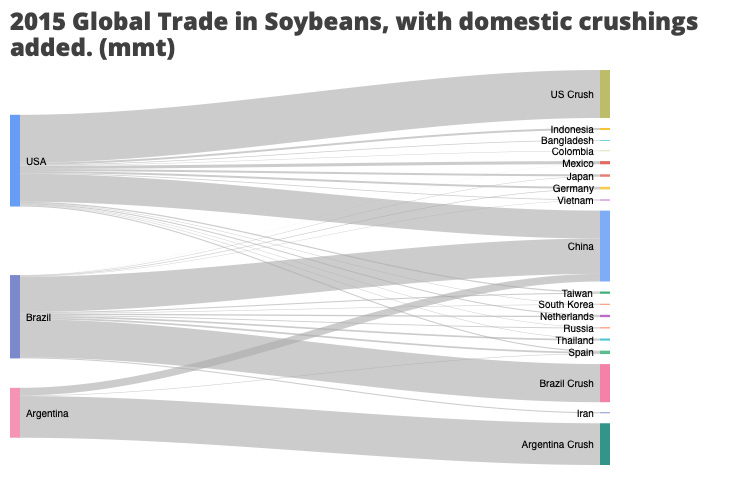

Looking at 2017, it is clear that agricultural exports to China play a large, and symbolic, role in our trade. But we are not the only exporter to China. Below is a diagram of the trade flows of soybeans from the major exporting countries to all of the major importing countries.

The diagram shows a few things, first, that China imports a lot of soy; 83.2mmt in 2015/16. Of that, 31.8mmt are from the US. Second, that China could not impose an embargo without seriously damaging domestic supplies of soybeans. (Not that I think that they would want to). Why? In the past, when such embargoes were imposed, what we saw were redistributions among international trade–Brazil, a non-embargoed nation, would increase exports at the expense of domestic consumption, and then ‘back-fill’ the domestic demand using imports from the USA. Such an arrangement would be markedly less efficient, and would require improvements in Brazilian infrastructure, and would ultimately result in lower prices received by US farmers and higher prices paid by Chinese end-users.

In addition to its 40.2mmt of exports to China, Brazil crushes 43.4mmt domestically. Of that, they export approximately half, mostly to China. Converting this to soybean terms, that means that there is another ~20mmt of domestically consumed beans that could go to China from Brazil. Similar calculations for Argentina indicate very little room for additional exports, as Argentina already exports roughly 90% of the meal that they produce. If Brazil and Argentina diverted all exports to China, there might be enough bushels to meet Chinese demand, but only barely.

Ultimately, such an embargo is nearly impossible because of the need for US soybeans to meet China’s demand. This doesn’t mean that a reciprocal tariff couldn’t happen, though. In economics, we like to think of tariffs as ‘wedges’ between the price paid and the price received. The ‘incidence’ of a tariff is who bears what portion of the wedge compared to trading without the tariff. There are a myriad of formal econometric techniques to estimate the incidence, but the intuition is always the same, whichever is more inelastic, supply or demand, will bear more of the cost of the tariff.

It’s not clear whether US supply or Chinese demand is more inelastic. Within a crop year, I suspect that US supply is much more inelastic, as crops have been planted, and the bushels need a home. For that reason, I would expect if such a tariff were imposed, at least 2/3 of it would be subtracted from US cash prices, through a combination of weaker basis and lower futures prices. Over multiple years, acreage allocation has more ability to shift to other crops than Chinese demand has to shift to other sources of protein. Therefore, I would expect to see the incidence falling on US farmers declining to 1/3 or less within one full crop year, and nearly zero after two.